Hello!

Welcome to #6! I'm pleased to report that the Connection has become quite

the international publication, with subscribers from New Zealand, Spain, Ireland,

Holland, Australia, Switzerland, Germany, Belgium, England, Canada, and the

Republic of South Africa, as well as people from all parts of the United States.

Thanks to everyone who's subscribed and participated in helping to make the

Connection better and better. As always, I welcome all your reviews, photos,

art work, classifieds, letters (a new feature), etc., for public consumption.

I hope all of you are enjoying your summer so far, and for those of you in Europe,

I hope you're all especially enjoying the many opportunities to see Luka since the

beginning of June. I didn't get the latest confirmed itinerary till after Issue 5 was

already out, and there lies the reason why many of the dates were not included

on the tour schedule page.

The month of June found Luka playing the London Fleadh on the 7th, as

well as the Hamburg Stadtpark in Germany on the 8th, the Berlin Loft on the 9th,

Bielefeld Kamp on the 11th, Hannover Capitol on the 12th, Münster Jovel on

the 13th, the Grömnitz Festival on the 14th (with Herbert Grönemeyer),

the Salzgitter Insel on the 16th, the Gummersbach Stadion Lochwiese on the

17th, the Duisburg Weden Stadion on the 19th, and leaving Germany on the

21st with a show at Trier Stadion.

After that it was on to Holland on the 27th, with Luka headlining at the

Deventer Festival. Finishing off the month, Luka played in Switzerland

at the festival in St. Gallen on the 28th.

At the moment the only confirmed tour dates I have for the rest of the

summer are the Midtfyns Festival in Denmark on the 2nd of July and the

2-day festival in Belgium on July 4th and 5th. In August, there's the

annual Feile in Thurles, Co. Tipperary, Ireland on the 1st, and on the

7th there's a festival in Sweden (check your local music paper/ticket

agent for more details).

At press time, unfortunately, I have no itinerary for any confirmed

US tour dates. But for any of you who'd like me to send you a

schedule, please send a self-addressed, stamped envelope. That way,

as soon as I get any news in about shows from now through October/November,

I can send you a schedule as well.

Remember Sassy magazine's review of The Acoustic Motorbike

by Christina that was reprinted in the last issue, where she went on to

say that she found (and I quote) "Lukums' Irish accent thrilling

and hilarious" while saying "sweaty and wet" on

"I Need Love"? Since then, I'd read in the latest issue of

the teen 'zine that when she went backstage at the U2 New York

show in Madison Square Garden this past March, that she

"was dissed by Luka Bloom and some other Warner Bros.

personnel" while shmoozing with all the U2-types, including

"The Bononator"' (read: Bono - where does she come

up with these nicknames, anywas??) I'm just wondering if Christina

found Luka's Irish accent "thrilling and hilarious" while

being dissed...

Tricia Fitzgerald reports that the video for "I Need Love"

is getting some air play on New Zeeland television.

There's a great review

of The Acoustic Motorbike in the latest

issue of Dirty Linen, written by Maureen Brennan. The quarterly magazine

is jam-packed with gig reviews, tour information, interviews and photos,

emcompassing all genres of traditional and contemporary Irish / Scottish / Celtic

music, as well as folk, reggae and world music. I highly recommend it.

As mentioned in last issue's Updates section, HEAR music catalog/magazine

features mini-reviews on both Riverside and The Acoustic Motorbike. It hails the

debut record as "the album that got us into Luka Bloom. We remember

the first time we heard one of these songs on radio. It was like a visit from the

Lone Ranger. We just kept saying 'Who was that Irish man?!' As soon as we found

out, we got us a copy of Riverside ...Luka couldn't have come at a better time."

HEAR also quotes Luka on his recommendation of Sam Phillips' music:

"Sam Phillips is a remarkable singer. Early in her career she opened for me,

and waiting to go on, she just stood there in her coat talking to people. 'Ten minutes',

she was told. She kept her coat on, kept talking. 'Five minutes' - same thing.

When she was told it was time, she took off her coat, walked on stage, started to

sing, and stunned everyone." HEAR describes her music as "Elvis Costello

playing with a sharpened number two pencil." Order her new record, Cruel

Inventions from HEAR, or any recording for that matter, and receive a

free CD sampler,

containing tracks from Luka, Lou Reed, Emmylou Harris, Daniel Lanois,

Maura O'Connell and Julee Cruise.

That's it for now. Enjoy the rest of your summer, and expect issue 7 by late

October/early November.

Pedal on!

June

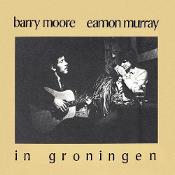

Double Dutch

Barry Moore had already made a name for himself in Holland with the release

of his debut album, Treaty Stone, in 1978, and after finding himself

increasingly isolated from the rapidly booming punk scene in the Dublin of

the late seventies, Barry, along with partner Eamon Murray, decided to move

to the far north of the Netherlands in search of new musical directions -

namely, a back-water town called Groningen. The result of this adventure was

an interesting album entitled, not surprisingly,

In Groningen. Although the

record lacks the sheer wonderment of being in a foreign place, (i.e.

Riverside) the record nevertheless has a moody, laid-back but pensive feel,

probably more in keeping with the location, and as contradictory as this

sounds, a similar emotion, albeit in a opposite direction as does Riverside.

This album was released on the Kloet label, which was, from what I can

gather, an arts group that ran a monthly alternative newspaper. In Groningen

contains some nice melodies and some unusually interesting guitar and

harmonica/saxophone arrangements. Aside from Moore and Murray, this project

also featured Gerhardt Ammerlaan on bass, Geert Oude Weemink on melodeon,

Buck Staub on, of all things, bodhran, and Olga Grooten's truly lovely flute

playing.

This album was released on the Kloet label, which was, from what I can

gather, an arts group that ran a monthly alternative newspaper. In Groningen

contains some nice melodies and some unusually interesting guitar and

harmonica/saxophone arrangements. Aside from Moore and Murray, this project

also featured Gerhardt Ammerlaan on bass, Geert Oude Weemink on melodeon,

Buck Staub on, of all things, bodhran, and Olga Grooten's truly lovely flute

playing.

The intro track, "Snowbird", begins the album with a haunting richness,

moody guitars accompanied by a soft rich harmonica, which echoes in the

background during the entire number. One interesting lyric in the song:

"My fortune is fire, but I'm in tune with the sea", echoes Barry's

long time fascination with bodies of water, which as we all know has continue

up to the present day. "Dog Among the Bushes" is your standard

Irish fare, a traditional type piece that demonstrates Luka's - sorry... Barry's

superb fretwork. This was probably the "Te Adoro" of its time, and

I found myself wishing he would beat the hell out of the guitar and really get

the tune rolling, but alas this doesn't happen.

By the time "One Last Cold Kiss" comes out of the speakers, the

album's major drawback becomes apparent, in that it lacks variety, and the

songs seem to follow the same basic pattern, which in retrospect is unfair of

me to criticize some fourteen years later. Given that this was recorded during

what was without a doubt, the most musically impotent decade in the history

of the human race, and considering what utter rubbish the general public

were placing on their turntables during the seventies, this is quite a minor

downfall. The album's best offering is the title track, "In Groningen",

a song that conjures up another familiar theme in the man's songwriting, that

is the stranger-in-a-strange-land saga: "Came into this city on a cold

winter's morn", isn't too far away from his later song "Cold Comfort"

(a song which sadly never made it on to vinyl) with its lyric "...on a freezing

New York night". The Moore things change, etc.... The vocals and fretwork

really shines on this song as does Eamon Murray who weaves a glorious melody

in and out of the guitar chords in a sinewy fashion.

Probably the most surprising song on the album is the re-working of "Danny

Boy". Like most Irish people (especially ones living in America) I can

honestly say I detested that song, but as corny as this may sound, I (gulp)

quite enjoyed this version. It sounds like a completely different song. Gone

is the obligatory Hollywood/stage Irish images it normally conjures up -

dare I say it? - he actually gives it some dignity, and now it strikes a

whole different chord with me. "Our Land" (and I know it is quite rude of me

to mention this fact) resembles a few of Christy Moore's songs, as does the

occasional slower songs on the album. Not to say that this is a bad thing,

but this was, as most people acknowledge, the major stumbling block to any

chance of Barry Moore making a successful career for himself as a solo

musician. It was no fault of his that his older brother was, and still is,

one of the most influential artists in the history of Irish music. But as we

all know now this turned out to be a blessing in disguise.

Although by no means in the same league as his later masterpieces, it's

still worth trying to get your hands on a copy of this record, but be

warned - you may find it easier to find the Holy Grail. In Groningen was

a one-off album that had plenty of talent but little if any potential and was

unfortunately already dated, considering that it was recorded at a time when

Joy Division, and The Fall were pushing into new areas of popular music, in

the same way that Luka is now destroying the stigma surrounding accoustic

guitars. Ah well, some things are worth waiting for.

By Steven Eccles

In The Kerry Mountains

The following interview took place in November 1991, in, of all places,

a bicycle shop in Dingle, County Kerry, just after the recording of the new album.

David Donohue, a Dublin musician himself, provides the questions, which were

then taped and edited for broadcast for Irish Television. It contained not

only this interview, but also featured Luka performing "The Acoustic Motorbike"

surrounded by some incredible scenery on the Dingle Peninsula, and later off

to an empty movie theatre, where Luka performed "I Need Love". We begin

with Luka looking back on the past couple of years of recording and touring.

Could you tell us what you've been doing since the release of Riverside?

You know, it's just great to be sitting here, the record finished, just

taking it easy and getting ready to do more madness on the road.

I recorded Riverside in New York and Los Angeles and then I went on tour for

most of 1990, which culminated in the end of November at the gig at the Olympia

in Dublin. That was the end of the tour. I went away then, just cycling

around the country, mainly around Kerry and a bit in County Clare.

Then, in January, I went down to Spanish Point to write a bunch of songs.

But at this time I was still thinking that I would probably record the album

in America, with an American producer. And I got the songs written. It was

only then I was starting to spend more time in Dublin. I'd been away from

Dublin for five years, working in America, and it just began to dawn on me

very quickly that Dublin had changed very dramatically, and I felt very much

part of Dublin and very excited about being in Dublin. And so I just

happened to be walking around Temple Bar, in the middle of Dublin. There's a

studio there called STS, where I'd done some recording before, and I knew

all the people in there, so I said, okay, I'll go in and have a chat with

the guys and see what's going on. And I did. Paul Barrett happened to be

working with this well-known, fourpiece garage band, from the northside of

Dublin called U-something-or-other and it just seemed to me that the work

that U2 were doing in STS Studio was very special (Achtung Baby early demo

tapes - ed.note) ...the atmosphere in there was very special. They were

working with Paul Barrett, a man who I've had a lot of respect for, but I'd

only really known him as an engineer. In fact, he'd been doing a lot of

production work over the years, but mainly I suppose in some sort of an

assistance capacity, because he didn't seem to be getting the credit as a

producer.

But I felt there was just something going on when I went in there that day,

that just changed my whole feeling, from one of not wanting to record an

album in Ireland, to all of a sudden, I really wanted to make an album in

Dublin, in this studio, with Paul Barrett producing.

U2 were going for a very raw rock and roll sound when they were there.

What were you looking for? What was in your mind when you walked in?

You see, I don't... I'm no good on judging studios in terms of what a studio

will give me. I can only really think in terms of "What's this room like to

sing in?" I've no sense of judging drum sounds or guitar sounds or anything

like that. It's all about atmosphere to me. It's 100% atmosphere. Other

people have to make technological judgements. I was looking for a buzz in

the area. When I recorded in RPM, when I recorded Riverside in New York,

there was just a buzz in the area that I really tapped into. And I felt the

same thing in Dublin. And this particular area, Temple Bar, was alive with

bands and music everywhere, and this studio was bang in the middle of it. It

just all felt right. Fortunately, Michael Hill of Warner Brothers was

familiar with The Stars of Heaven, and loved The Stars of Heaven, who were a

band that Paul Barrett had worked a lot with, and became very excited about

the idea, even though they knew nothing about the studio, and so it just all

fell right into place. Very surprisingly, from being a situation where I was

determined to work with a American producer in America, and just like that,

the decision was made. It's been very much a coming home process for me,

it's full circle. Because five years ago, I left Ireland completely and

totally. And then all of a sudden, in one day, making a decision, that I

want to work here, in the center of Dublin, with an Irish producer.

Do you think Dublin has changed a lot in the last five years?

Very dramatically, yeah.

What is it, do you think?

I think a lot of it is the inhibition, the creative inhibitions that Irish

people are notorious for. I mean, there are so many stories of Irish people

leaving Ireland and going to America and discovering their creative flow.

More and more I find in the last year that young Irish people particularly

are doing just that at home. They're not inhibited, they're not afraid,

they're not intimidated by the business, by record companies. They're not

intimidated by management. They're not intimidated by decisions or about

their own performances, or their own writing. They're just going for it in

the way that people have been going for it in New York or Los Angeles or San

Francisco, for decades. They're finally starting to do that, in Dublin, and

all over the country.

I wanted to find an atmosphere that would help me to feel a sense of

performance. Because that's what I am. I'm a performing songwriter, as

opposed to a recording artist that does the odd show.

You had tried out quite a few of the songs, live, beforehands...

I haven't had much time to try out this batch of songs. Two or three of the

songs on this record were written, literally, as I was going into the

studio. And one of them was completed in the studio. So that was a new

experience for me, to actually have new songs being recorded before they

were performed. I like to test songs live before I record them.

So what about the "Acoustic Motorbike" thing...

Where did that come from?

I was standing outside a restaurant near where I lived in Greenwich Village

after we'd finished Riverside with my manager Tom Prendergast and ... I

can't remember if his partner Glenn was there, but Michael Hill was there,

and we were just talking about my music and the whole idea of this guy being

alone with a guitar not playing traditional folk music, but it being a very

contemporary thing. And we were also talking about bicycles, because I've

become a bit of a bike freak, for lots of different reasons and we just got

talking about this... and somewhere along the course of the conversation,

I was talking about how Harley Davidsons were a symbol of rock and roll

and the mountain bike feels like the symbol for what I do, how it's all very

organic, and it's all very mobile and fluid, and Tom just came out with this

phrase, the acoustic motorbike, and it stuck in my mind. I never dreamed

of it really being an album cover, I don't think. But I certainly didn't intend

it to become a song, until I did all the touring last year. One of the

things that horrified me on the tour last year that was I felt that

everywhere I went, every city I went to, whether it was in America or

Canada, Europe or wherever, the one thing that I saw that horrified me most

of all was just too many cars. There just seemed to me to be just too many

cars in the world. And particularly this year, with people going out to the

Gulf, to do battle over oil. I felt I wanted to, more and more, bring the

image of the acoustic motorbike into my work. And it just became a cool

image then. It just became something for me that fits in my music. It ties

in with what I do. And I wrote about this cycle I took in Kerry in November,

and called it "The Acoustic Motorbike". So there you go. (A chuckle and a

broad smile appear on Luka's face.)

What about you cover of the LL Cool J song, "I Need Love"?

Well, one of the reasons for initially seeking out a song like "I Need Love"

to learn was that as a solo artist, it's very easy to be categorized and I

detest categories of any sort. I believe the whole purpose of categories now

has just become completely redundant - simply because there is so much

crossover going on, in styles and influences, and to be boxed as a folk

singer in a sense is a kiss of death for someone like me, because I want to

play for audiences who want to hear bands. I wanted to find something that

people would least expect an Irish semi-acoustic singer songwriter to do.

I'd been living in New York for a while and been hearing a lot of rap and I

wanted to give it a lash. I found this to be a very challenging song - the

most challenging song I've ever learned, so much so that when I tried to put

it on Riverside, it just wasn't ready. I just hadn't got it. It took me a

year to get the performance of this song right. It's the most complex song

I've ever learned and what's interesting about it now is that having learned

it and sung it a lot, it actually doesn't feel like such an alien thing

anymore because Irish people are story tellers traditionally and so the idea

of telling stories and talking over music is a traditional thing in a way,

which is sort of hilarious when I think about it because I did the thing to

get away from folk music in a way. And yet the more I do it, the more I

realize that some of this stuff is really... I'd go so far as to say that in

some respects rap music is possibly the closest thing to folk music there is

left in the world because you hear people talking about life on the street,

as it is, now, today, which is traditionally what folk music was all about.

And very few people are doing that these days apart from Public Enemy, NWA,

and The Jungle Brothers, who I really love. In certain respects these people

are actually the real folk musician of our time and I didn't realize any of

that or think about any of that when I learned this song. But they were sort

of the general reasons why I wanted to learn it, but ultimately I stuck with

it because I loved the song. I just think it's an incredible piece of poetry

and great drama, and there's a great sense of somebody trying to come to

terms with their life and their sexuality and all that stuff.

And you think if you hadn't spent time in New York... I mean, did being in

New York actually draw you into rap? Is that where you started listening to

rap, or do you think it was just a great song that you happened to hear?

Definitely living in New York. I mean everywhere I went it was what I heard.

You know yourself from living in New York. It was what you hear from the

cars in the middle of the night. It's blasting out of everywhere. It's great.

I love it. Listening to all that stuff and just being in New York it just changed

my attitude towards everything and but most importantly towards myself,

in the way I play and the way I perceive the performances and stuff like

that.

Do you miss that kind of music madness that you get in New York while

being in Dublin ... walking up the street hearing 20 different types of

music from different cultures...

No. I don't. I kind of feel that after so many years of trying to figure out

where the hell I should be, I feel very comfortable being in Dublin. And I

feel really glad that I have spent the amount of time that I have in New

York so much so that I always look forward to going back. I always look

forward to going to America. I love working in America. And I do feel

a great sense of privilege of being able to come home. That means an

awful lot to me, because initially I never really wanted to leave Ireland.

I loved always being here. It was a matter of necessity. I had to get the

hell out of here in order to survive. But I'm in this great position now

that I've been able to come home and see my family and there's so

many people in America from Ireland who aren't able to do that,

so any feeling I have of missing the buzz of New York's streets

is balanced out by that. There's a groove in Ireland, you know.

There's an energy here. It's more subtle ... it's not as

"out there" but there is a very beautiful groove

going on here and I'm just ...

I sort of feel a part of it in a way that I never did before.

Song of the Brave

Luka's "Rodrigo Is Home",

recorded back in 1988 on his debut album on Mystery Records, tells the story

of nineteen year old Rodrigo Rojas, burned alive on the streets of Santiago

by members of the Chilean armed forces. Diana Theodores spoke with

Rodrigo's mother, and the following is an edited transcript from the original

piece, as published in 1988 in Dublin's Hot Press, as part of their

"Front Line" column. Luka was currently on tour in the US

with Hothouse Flowers at the time of this interview.

Chile was worlds away

But you could see it in his eyes

Growing up in the USA

Longing for Santiago

Rodrigo wanted to be where the action might be

Careful, Rodrigo, they said

Don't worry, what could happen to me?

It's Monday night in a club called Dylan's in Washington, DC, and

the place is packed. I'm here with Luka Bloom - it's his gig and he's

uncharacteristically nervous as he goes on stage.

In the audience sits a dark, intense woman, quietly sipping her drink. Her

eyes never leave the stage. She is Veronica Rojas De Negri, the mother of

Rodrigo, about whom Luka Bloom wrote the song, "Rodrigo Is Home".

Sitting at the table with Rodrigo's mother is Isabelle Letelier, the widow of

Orlando Letelier, the Chilean ambassador who was assassinated by Pinochet's

agents in Washington, DC, over 10 years ago.

Luka Bloom introduces his song. Veronica clasps Isabelle's hand tightly over

the table - two sisters in political refuge. As Bloom ripples into the

opening verse of his poignant song, Veronica's eyes fill with tears. She is

hearing the song for the first time. The song about her beloved, dead son.

As Bloom strikes the last chord, the place erupts. Veronica applauds

vigorously while she cries and she tells me her "heart has been

torn out".

Chile grew dim in the mind of an American man

The voice inside the child cried, "Return"

Rodrigo is home

When Chilean president Salvador Allende was shot through the head on

September 11th, 1973, Rodrigo Rojas and thousands of others could not know

what extremes of brutality they would confront under the military government

of General Augusto Pinochet. It has been fourteen years and the violence is

not yet over. Violence is even categorized with terms like "los

degollados" - the ones with slit throats - "los ahogados" -

the drowned ones - and, the ones we hear about most often, "los

desaparecidos" - the disappeared. ("Hear their head beat /

Hear their heart beat.")

When I go to visit Veronica Rojas at her apartment, I knock and wait a long

time. I hesitate to pound on the door because, I imagine, the sound may

frighten her. After two years imprisonment and torture in the hands of the

Chilean police, she would have cause to be shaken by the sound of aggressive

knocking. So I wait.

Eventually, the door opens and Veronica invites me in. She sits me down in

front of her photo collection while she gets herself ready. The photos

document the life of her son: the little Rodrigo, the adolescent Rodrigo,

Rodrigo the young man, Rodrigo's funeral. A bright flash of sunlight streaks

across the room and I glance around. The small apartment is a lush

mini-jungle of plants and the place is crammed with pottery, chimes, bright

coloured cushions, books, records and pictures - a cheerful bohemian space

in which there lives a woman with such a tragic tale to tell...

Soldiers hunt in packs

And cut down little children

In the city of deadly silence

And sickening screams

One young Chilean soldier smiles to his friends

And douses Rodrigo's body in gasoline

Veronica Rojas speaks of Rodrigo in the present tense. "Rodrigo loves

music... Rodrigo takes very good photographs... He is dead", she says.

"But he is still my child." She knows that, for now, she cannot

go back to Chile, even to put flowers on her son's grave.

Rodrigo Rojas grew up in a middle class home. His father, Ramon, an

inspiring politician, was noticeably absent from the scene. He had abandoned

Veronica over the birth of Rodrigo - a child he never wanted. Still, the

household was bustling with uncles and aunts and attention and conversations

that focused on politics. Veronica leaned to the left, was involved in

feminist issues and supported Allende. After Pinochet's overthrow, she

helped families of the "disappeared".

When Rodrigo was eight years old his mother sent him to Quebec to visit

relatives. Soon afterwards, in the year 1975, she was arrested in her home.

Rodrigo would not see his mother again for two years. While he struggled

with French and a new life without her support, Veronica Rojas suffered

unimaginable physical and psychological assault in prison - morning, noon

and night... Somehow, "by learning to become a brick wall" as she

describes it, Veronica survived. After her release in 1977 she was reunited with

Rodrigo and her young son, Pablo, who was born just before her arrest. They

moved to Washington, DC, amidst a community of other Chilean refugees.

Chile grew dim in the mind of an American man

The voice inside the child cried, "Return"

Life in Washington was very, very tough. "We had no money, not even for the

bus", recalls Veronica. "While I learned English, Rodrigo looked after Pablo

and struggled with yet another new way of life. He couldn't cope with what

had happened to me. He shut it out and he often shut me out. I knew that he

loved me but part of him blamed me for what happened to us - for having to

leave the Chile he remembered as a child and live with such hardship."

By all accounts Rodrigo was an exceptional boy. Veronica describes finding a

diary written by Rodrigo when he was only six years old: "I will start to

write a little of my life on each page... I was thinking about moving to

the right wing of politics but I can't leave the left because I can't

understand the suffering of the people... I also thought of buying a place

and building a happy city."

"When I found this little diary", says Veronica, "I cried

and cried."

"Rodrigo wanted to know everything, everything", she adds.

"In Washington he spent much more time in the library of Congress

than he did in school. He was scientific, artistic and musical. He used to

spend hours and hours listening to classical music, playing the charengo

(a ten string Inca Indian instrument) and reading poetry. But photography

was his greatest love."

Veronica shows me an extraordinary collection of self-portraits and various

scenes taken by the child photographer. "Rodrigo was unhappy in

Washington. By the time he was sixteen he was rebelling against everything

and everybody." School life at Wilson High bored Rodrigo. It seemed

to trivial. So he quit.

Taking photographs, talking about Chile amongst his small circle of friends

and dreaming and planning his return there took up most of his time. Against

all advice from his family and friends, the nineteen-year-old Rodrigo

finally realized his dream and took off for Chile with only his camera and

his naivete - memories of Chile, the romantic fragments of a childhood, lost

to him forever. As Washington journalist David Remnick put it, "Rodrigo

saw himself as a photojournalist and wanted to be where the action was

going to be..." Within a week of his arrival in Chile, Rodrigo photographed

the funeral of a nineteen-year-old student killed by the police at a

demonstration. "It was like he was taking pictures of his own funeral",

says Veronica.

Six weeks later, Rodrigo with his camera and a friend, Carmen Gloria

Quintana, were at a protest in another part of Santiago. They were separated

from the crowd by members of the army, dragged down an isolated alley and

unmercifully beaten with the butts of machine guns. Then they were forced to

lie face down on the pavement, drenched in gasoline and ignited. As they

writhed in flames the soldiers stood by and watched, chatting and laughing

amongst themselves. That was July 2nd. Rodrigo died on July 6th, after days

of suffering beyond human imagination.

Carmen Gloria survived and was exiled to Canada where she is still

recovering. Veronica's account of her trip back to Chile to watch her son

die and about the police brutality even at Rodrigo's funeral, using dogs and

tear gas and water cannons while 5,000 people mourned, is told to me in

struggling fits to maintain her composure. "November 2nd in Chile is called

"El Dio de Los Santos", and everybody goes to the cemetery from

all over to visit their loved ones. Here I am stuck. It is a very painful thing,

not to be able to go to the cemetery of your own child."

Rodrigo is home

Rodrigo is home

"The government is not giving justice to Rodrigo but his own people

are. And that to me is more important. Those criminals will never be punished.

But I have my own justice."

Veronica Rojas now works as a Youth Service counsellor - the only Spanish

speaking counsellor helping with cases of refugees, battered women and

others in hardship. She regularly tours the USA on speaking engagements,

telling her story of Rodrigo, "not for pity but because I want to do

something", she says. "We must stop these crimes. We must protest.

I don't want other kids to suffer like Rodrigo. There is so much to be done.

The meaning of Rodrigo's death is not about a single death. It is about the

tragedy of the Chilean people. And it could happen here and in Ireland too."

"Luka's song is not an invasion of my privacy. Even though Rodrigo is my

kid, it is a universal event", she adds. For Bloom, performing the song he

wrote after reading about Rodrigo's case, "always bears a sense of tragedy -

as though I were breaking the news to her. In a way, Rodrigo's creativity

was his crime."

Veronica tires, so the interview draws to a close. She has many miles to go

before she sleeps. "I was very moved to see Luka living what he was singing

and playing when he performed the song. I feel that is justice. Rodrigo

would be very pleased to know that maybe his death is an awakening."

This album was released on the Kloet label, which was, from what I can

gather, an arts group that ran a monthly alternative newspaper. In Groningen

contains some nice melodies and some unusually interesting guitar and

harmonica/saxophone arrangements. Aside from Moore and Murray, this project

also featured Gerhardt Ammerlaan on bass, Geert Oude Weemink on melodeon,

Buck Staub on, of all things, bodhran, and Olga Grooten's truly lovely flute

playing.

This album was released on the Kloet label, which was, from what I can

gather, an arts group that ran a monthly alternative newspaper. In Groningen

contains some nice melodies and some unusually interesting guitar and

harmonica/saxophone arrangements. Aside from Moore and Murray, this project

also featured Gerhardt Ammerlaan on bass, Geert Oude Weemink on melodeon,

Buck Staub on, of all things, bodhran, and Olga Grooten's truly lovely flute

playing.