|

Irish Emigrant Online - July 1989 | February 1990

The Irish Emigrant - Music

Reporter: Richard O'Shaughnessy @ GAO

July 17, 1989 - Issue No.128

- Luka Bloom (a pseudonym for Christy Moore's younger brother Barry) is back in Ireland

again after a year in the States recording for two albums and supporting the Pogues,

Hothouse Flowers and In Tua Nua. He's already started a tour with more dates to be

announced. The last time I saw him, I was a protesting student demanding college

authorities to 'freeze the fees'.

February 11, 1990 - Issue No.158

- Luka Bloom (brother of the man in black himself, Mr Christy Moore) has released an

album which is receiving good critical reviews and quite a deal of newspaper attention.

The great BP Fallon interviewed him for the Tribune, and he also received a large

piece in the Independent.

www.emigrant.ie

Hot Press - 25 February 1990

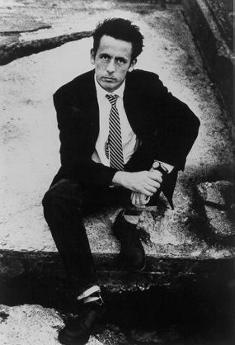

Into The Arms Of America

Deciding he'd achieved as much as he could within the confines of the music

scene in Ireland. Barry Moore changed his name, packed his bags and

took off for the USA. There, as Luka Bloom, he was fjted for his live

performances, awarded a major international record deal and his debut album,

Riverside, given the four-star treatment by Rolling Stone. On a visit home,

he tells Bill Graham about his emigrant s success story and explains how a

man who was regarded as a folky in Dublin came to cut a rap track in New York.

It's the standard hotel interview scenario as the record company person

solicitously nursesmaids the pair of us. Alongside the debris of earlier

dialogues the biscuit-tray, the drained coffee-cups, the empty Perrier and

beer bottles is a copy of a Rolling Stone record review, hot off the

fax-machine, a glowing notice that describes my companion as a decidedly

artful musician who s gathered a reputation for his electrifying live shows

and whose soaring major-label debut album is a dazzling entrance.

Later, standard practices continue as this decidedly artful musician ponders

the trappings of his newly-discovered fortune with typically chirpy

bemusements like his Burlington Hotel suite with its round double-bath,

hardly on the Playboy Mansion scale, but far from where he was reared and

the limousine the record company charters to convey him home whereas once,

he took public transport.

Later, standard practices continue as this decidedly artful musician ponders

the trappings of his newly-discovered fortune with typically chirpy

bemusements like his Burlington Hotel suite with its round double-bath,

hardly on the Playboy Mansion scale, but far from where he was reared and

the limousine the record company charters to convey him home whereas once,

he took public transport.

And this is a guy who also needs two bases, one in New Jersey, the other in

Dublin. But he isn't some tax-exile tourist, a passage migrant wintering out

in Ireland. This is an Irish emigrant who s sustained by and has gained from

his double-life. Barry Moore renamed himself Luka Bloom and finally found

fate giving him a wink, a friendly nod and a free pass.

His story is both heart-warming and an example to anyone who's ever felt

their career has been stuck in an Irish bog. Throughout the Eighties, the

old-style Barry Moore was numbered among Dublin's also-rans, a charming

man but one of life's support acts, a junior member of the Irish folk contingent

who seemed trapped in a perpetual state of transition.

Caught between generations, codes and cliques, Moore knew the Irish

singer-songwriter school had got stultified and needed to be rescued from

its ingrained habits. But without acceptance and clout, within the new rock

circles, he found few allies who sympathised with his vision.

So, in the last throes of desperation, he changed his name to Luka Bloom and

high-tailed it to America. Lo and behold, the Dublin duckling was

transformed into a New York swan, returning with a Warners contract and a

skilled, light-fingered album, Riverside, that s genuinely innovative in its

spare but sleekly atmospheric mix of acoustic guitar and responsive percussion.

So, Luka, cad a tharla?

It would take a prodigiously sainted man not to score some points about his

previous neglect. It would also take an insensitive, tactless journalist not

to realise this Luka Bloom story starts in the sump of his earlier Dublin

disregard.

When I changed my name, he says, I had surrendered to the fact that I wasn't

going to create anything in Ireland that would let me perform and record in

an international arena. So I just decided to get out. And initially, it was

very painful because I am, and always was and will be, very rooted here for

family reasons and just reasons of loving living in Dublin. But I just felt

in this unbelievable rut.

Psychologically, he felt stymied by the incestuous nature of the Irish

scene. His face had become too familiar. In America it was different. I didn't

have the psychological baggage of the Hot Presses and In Dublins and other

people around who I would allow myself to get fucked up about, he observes.

You know how so many people in Dublin are so self-conscious because you

write songs and you walk down the streets and you see those people who would

be reviewing those songs when you perform them. So there's this constant

sense of being closed in. A sort of Valley Of The Squinting Windows thing.

And in America, I was completely liberated from that.

Actually his name-change, first suggested by Billy Bragg's manager, Peter

Jenner, happened in Ireland. Equally he actually left Ireland twice, the

first time temporarily just after he recorded his 88 debut album, Luka Bloom,

for Mystery Records, a trip taken deliberately, he stresses, because he

could only get used to being the stranger, Luka Bloom in a strange land.

But that album was a victim of the political and contractual shenanigans

between Mystery and their Irish distributors, WEA that flared after the

multinational's former managing director, Clive Hudson's departure. It wasn't

so much released as limped out to the shops and hardly helped his cause.

Besides he now says, that album sounded out of date three months after I

recorded it though I don't mean to denigrate the people involved in it. It's

more a reflection of me it's just that my whole mentality changed very

dramatically within three months of going to America.

Possibly decisions were still in the balance when he first returned home to

Ireland but the Mystery/WEA feud forced his hand. At the time, Luka recalls,

it was very traumatic but it also proved to be very productive because it

precipitated a sort of a rock-bottom of despair which made me sever all my

relationships with everybody in Ireland in a professional capacity and, like

the other emigrants, jut get out of here.

In America, Luka now believes he was in the right place at the right time

for the first time in my life. Tracy Chapman and Michelle Shocked had

launched the new acoustic aesthetic but there were few males to match them.

Certainly none with Luka's combination of freshness and his hard-won

performing experience and expertise. This time, the drudgery of hiking

himself and his guitar around Ireland actually worked to his advantage. He

agrees: I couldn't have done what I m doing now when I was 24 I would have

blown it. And assessing his American competition, he continues, calmly and

without any over-inflated sense of himself:

To be honest, most of the solo artists I encountered in America, were still

doing Simon And Garfunkel stuff. You're absolutely right. The standard of

solo performance I've encountered in America hasn't been all that great. But

I also have to say to you that the reason this particular situation happened

for me was because I never worked as a solo artist. I think of my instrument

as a band, as an instrument of noise. I don't treat it like a six-string

Gibson traditional thing. I think of it as a means to make noise. My whole

outlook is to try to create the dynamic of a band. And that's what makes it

different. I don't think it was just because I was working in a more

difficult arena in Dublin.

Luka will own up that he suspected it was a propitious time to try his luck

in America. Otherwise he had no masterplan beyond a determination to avoid

demos and instead promote himself through live performance. The Mystery

album didn't enter his scheme.

He found a management team in Glenn Morrow and Tom Prendergast, the latter a

transplanted Limerickman, and won support slots with The Pogues, Hothouse

Flowers and The Violent Femmes. Finally, without any reference to Dublin,

Warner's New York office bit.

The years of neglect in Ireland initially made him suspicious, Luka now

concedes: I went in to my first meeting with Warners totally suspicious,

aggressive and uptight and they listened to me for twenty minutes and then

they said, we don't know what you're talking about, we've come to your shows

six or seven times, we love your gigs, your songs, your approach, we want to

sign you, what's your problem?

So I kind of went Oh! And since that time, everyone who's worked with me on

this record has worked with a view of understanding and then fulfilling my

dream and we did it.

Going to America changed Luka Bloom's fortunes; it also affected his music.

Riverside may be bare but it isn't spartan or impoverished. Like Mary

Coughlan's forthcoming album which was recorded in London, Luka Bloom's

music has been refreshed by the change of partners and venue. Too often,

Irish singer-songwriter albums can fall victim to a false democracy where

everyone pitches in with their stock licks. But Luka's New York players knew

the value of underplaying, understood that sometimes a song needs only a

kiss on the cheek.

His own philosophy was also transformed. Nobody would have connected the old

Barry Moore with rap yet in the new guise of Luka Bloom, he actually

performs an LL Cool J song, I Need Love. Says Luka, I deliberately set out

to learn a song that would be known to people but that in being known to

people and knowing where it came from, it would automatically take me out of

that folk bag so people would know this guy's not trying to be the next James Taylor.

Living in Hoboken, New Jersey, only a mute hermit could avoid rap: I didn't

do that stuff in Ireland because I wasn't exposed to it. But being in

Hoboken, just outside of Manhattan, that's the music I heard on the street

all day with the kids coming down the street in their cars with the roofs

off and these huge powerful systems in them. So it's LL Cool J, Tone Loc

and Neneh Cherry all day.

But I Need Love isn't included on Riverside. Luka thought it might deflect

attention from the remainder of his work: I wanted to make an album about

just me and my songs.

Riverside is a genuinely Transatlantic album, sometimes tempered and

transfixed by an emigrant's wonder at America. An Irishman In Chinatown, a

waggish crowd-pleaser live, doesn't have the weight to survive continual

listening on record but both Hudson Lady and Dreams In America

are more substantial exactly because they're less literal. Of the latter, Luka explains:

I wrote it as a result of encountering for the first time, the vastness and

sheer physical beauty of America because when I travelled with the Hothouse

Flowers we had one long drive through the Rockies. I was just completely

overwhelmed and I suddenly realised that when people talked about the

greatness of America, it wasn't just a right-wing political thing.

I wrote it as a result of encountering for the first time, the vastness and

sheer physical beauty of America because when I travelled with the Hothouse

Flowers we had one long drive through the Rockies. I was just completely

overwhelmed and I suddenly realised that when people talked about the

greatness of America, it wasn't just a right-wing political thing.

In the song, I wanted to create a panoramic feel but I wanted to do it

acoustically and that was the exciting challenge. And I also wanted to write

about the fact that as an Irish person, you always find yourself thinking

about the emigrants and the pioneers. Apart from the fact that they wiped

out a civilisation of wonderful people, there's this other aspect of them

which is very beautiful this great spirit that took them across the

continent. And I wanted to capture that sense of rootlessness and loveliness

and sadness that you always find in America. Because you also find that if

people had an Irish or a Russian background, they're very nostalgic about it.

Luka Bloom is equally expansive explaining other songs on Riverside. Like The

Man Is Alive, whose first verse recalls his father's death when he was only 18 months.

It was the newest song on the album and it was also the most important

because it covered the most important subject-matter in my life. It came

about because of a very strange meeting I had with a woman in Vancouver

who'd had the identical experience. And we also had the same birthday as it

turned out. And she was also a songwriter and the youngest in her family.

There were so many similarities but what was different was that she had an

entirely different attitude to her father and his death. I actually learned

something from her that opened up a relationship with my father that I'd

never had because I realised that my father didn't go and leave me behind.

Everything he left behind, he passed on to different people who passed it

on to me.

Potentially more controversial is The One with its stinging refrain: Why

should you be the one to go out on the edge / Do you really want to be another

dead hero? Luka concedes the song was inspired by Shane MacGowan but he

insists he had other targets in mind. Like the voyeurs and parasites on

another man's wound of fame.

I said to somebody earlier on that there's an aspect of the rock n roll life

that's very reminiscent of boxing. Like there are people who derive a

certain voyeuristic pleasure in watching other people go under.

He also defends himself against accusations that the song merely restates

the obvious: I know that and from a critical perspective, that annoys and

bores people And it sounds throwaway. But sometimes the obvious is not so

obvious. And sometimes the obvious is needed. I didn't want to write an

intelligent, deep, thoughtful dissertation. I wanted to articulate a genuine

sense of anger.

Luka Bloom's American sojourn has made him caustic about aspects of the

business. Tracy Chapman, or more accurately her entourage, get the back of

his hand: To be honest, I actually think that was something that was very

seriously manipulated, that actually became a very cynical exercise. Like

the fact that she was a young black kid from Boston was really exploited on

her behalf in a way that may have been detrimental to her. I found myself

not trusting or believing it after a while.

But maturity and his new horizons also brings the gifts of insight. Like the

time he first encountered his Iranian percussionist, Ali Fatemi.

You don't have to pursue anything in New York. Just simply living there

means you're bombarded by the rest of the world. If you don't have time to

see the world, just go to New York So I found myself being invited to see

this Iranian combo in Columbia University and it was just two guys. And it

was in this reverent, church-like environment though the music was

light-hearted just like a folk club and only afterwards did I realise it was

total improvisation, a sitarist and this percussionist with finger drums.

And sometimes when I closed my eyes, it just sounded so Irish or so

potentially Irish.

I think, like everything else, my ears have opened up a lot, he says. I used

to have a very arrogant attitude to music which, like all arrogance, is born

out of ignorance. I felt I didn't really need to listen, but one of the

things I discovered in New York was the joy of listening and the joy of

learning. All the possibilities that you can do anything with a song.

Looks like Luka Bloom has found his world, his oyster and his pearls.

Bill Graham

© 1990 HOTPRESS - www.hotpress.com

The New York Times - March 21, 1990

The Pop Life

Luka Bloom at Tramps

Two years ago, Barry Moore, an Irish folk singer who had been performing in

his native country for eight years and felt he was going nowhere, decided

to change his name to Luka Bloom and begin again in the United States.

"I wanted a name that was as pretentious as Iggy Pop or Bono or Sting,

that didn't mean anything but that had a good sound," he recalled the

other day. "It was a total joke."

His first name was adopted from Suzanne Vega's hit song "Luka".

The last name came from James Joyce's Leopold Bloom. And if the name was

a joke, it still helped Mr. Bloom to get a new musical lease on life. In a short

time, he built a reputation as one of New York's most exciting acoustic folk

performers, and the word of mouth helped win him a record deal on the Warner

label Reprise, which recently released his debut album, "'Riverside".

Tomorrow evening, Mr. Bloom will appear at Tramps.

"Riverside" is an effervescent collection of original songs with

subject matter ranging from an upbeat contemplation of the suicide of

Picasso's widow, Jacqueline ("Gone to Pablo"), to the surreal

experience of moving to New York and observing its street life ("Hudson

Lady").

"I wasn't interested in writing about Picasso the artist," said Mr. Bloom

about the song "Gone to Pablo". "What attracted me was the story

of this woman who lived in isolation for years after he died and ultimately surrendered

to the sorrow of life without him. Although people view suicide as a selfish, cowardly

act, I felt there was great dignity in her passing away and a sense of hope in her

being reunited with his spirit."

It is only in the last several years, Mr. Bloom said, that he has found his style.

"While in Ireland I ended up boring the pants off myself with the music I made,

which was sensitive, folk oriented and nonchallenging," he recalled. "Then

when I started doing something interesting, I found myself ignored. That was when

I realized I had to leave Ireland and change my name."

The exuberant acoustic style that Mr. Bloom evolved was inspired partly by the

post-punk rock of Irish and Scottish bands like U2, Simple Minds and the Waterboys,

three bands he said he admired because he found their music "very direct,

passionate, lyrical, and people oriented".

"I spent a couple of years trying to find a way to bring myself into this

music," he said. "First I tried a band, but I couldn't get the right human

chemistry. Finally I took what I learned from working with a band and blended

it with the intimacy I cul"

Stephen Holden

© 1990 www.nytimes.com

The Georgia Straight - Music - April 27 - May 4, 1990

Bloom Seeks Rock Fans

"Clueless" folkie goes from opener to headliner.

Irish folksinger Luka Bloom had to come to the U.S. to find a new name ...

and the confidence that is rapidly making him one of the most perceptive performers of the moment.

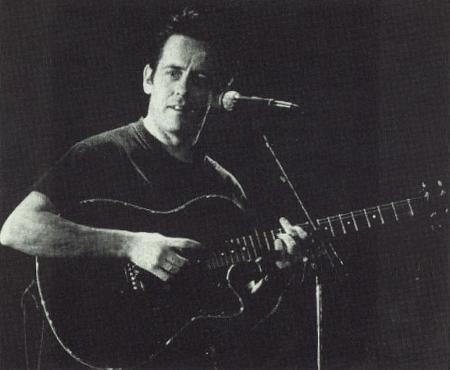

With a combination of intoxicatingly percussive guitar, a deep bagfull of

haunting melodies, and an unusually thrilling voice, Luka Bloom would be the

freshest thing to hit the folk scene since Suzanne Vega ... if he cared

anything about such a scene.

"I don't like to consider myself part of any traditional music world,"

said the Irish singer/songwriter in a recent call from London, England.

"I seek out stand-up rock audiences, because I like that kind of energy. I'm

not out to soothe some passive crowd of folk worshippers. They have to like

a fair bitta noise: I play acoustic guitar, but I tend to play it loud."

With a combination of intoxicatingly percussive guitar, a deep bagfull of

haunting melodies, and an unusually thrilling voice, Luka Bloom would be the

freshest thing to hit the folk scene since Suzanne Vega ... if he cared

anything about such a scene.

"I don't like to consider myself part of any traditional music world,"

said the Irish singer/songwriter in a recent call from London, England.

"I seek out stand-up rock audiences, because I like that kind of energy. I'm

not out to soothe some passive crowd of folk worshippers. They have to like

a fair bitta noise: I play acoustic guitar, but I tend to play it loud."

As the younger brother of Irish music superstar Christy Moore (Luka Bloom

took his first name from the well-known Vega song and his second from James

Joyce's central character in 'Ulysses'), this raising star has forged his

own path into genreless territory. And, like a song title on 'Riverside',

his Reprise debut album, he's "Over the Moon" about his fírst flush of

success, something he talks about with his mild, softspoken accent,

punctuated frequently by a staccato Woody Woodpecker laugh.

"I just finished my first tour of Europe, with the Cowboy Junkies, and I'm

amazed at how quickly people have picked up on the album. I played in

Holland last night, for the first time ever, and 600 people were there and

they knew all the words to my songs."

Bloom has made several trips across Canada, building his own audience while

opening for Hothouse Flowers, the Pogues, and the Violent Femmes, but has

only recently become a headliner: he's supporting local faves Spirit of the

West at the Commodore Friday and Saturday (May 4 and 5), then booting across

town on the second night to his own gig at the East Side's WISE Hall, with

songwriter Bill Morrissey opening.

Bloom has written songs for 20 of his 34 years, and one thing that has

elevated this tunesmith above the average strummer is his abiding

musicality, more so than the expert storytelling that characterizes many of

the folk ghetto.

"I guess my aggressive style is a bit of a trademark, but I also use a very

full, open sound for a lot of my slow tunes, and I really value dynamic

variety in my performance - or anyone else's, for that matter."

Zippy but sparsely accompanied songs like 'Rescue Mission' and 'Delirious'

make ideal single choices, especially because their lyrics and music are so

concise. "If you can say it in three minutes, why take six?" Of

his next album, Bloom says, "It would be easy right now to go into the

studio with a bunch of very cool musicians and come out with a 'safe' record.

But, if anything, it will probably be more raw."

"Actually," he says after a considerable pause, "I haven't a

clue what I'm gonna do next."

Initially, the artist avoided record-company types, worked on his live

performance, developed a street buzz, and eventually the biz came to him,

giving him a choice between labels. But along the way, he's had to deal with

the pros and cons of living in Moore's shadow.

"I think the most important thing I've learned from Christy has been to

respect my audience. That's one of the things I admire most about him, that

he has great love and respect for his fans, up and down the line. I have

watched aspects of his career and learned a thing or two, I suppose, but our

approaches are ultimately very different. Bein' his brother may have been a

problem for a while, back in Ireland where he's so very well known, but not

elsewhere or today."

While Bloom cities some examples of Irish artists who have made it big in

Britain, he says it remains an alien experience.

"It is somewhat difficult for an Irish person to break past the sense of

being an immigrant in England, and just a person who writes songs. I've

heard people talk about the experience of being a black performer in the

United States, and sometimes I have felt that way as an Irishman in England."

Like horizon-seeking Irishmen before him (U2 is an obvious example), Bloom

felt profoundly changed by his initial visits to the U.S.

"Just around the time I changed my name, everything else changed as well."

Bloom giggles at this ass-backwards recollection, but he describes a solo

jaunt to Washington, D.C. in 1987 as a surprise point in developing a whole

new attitude.

"Not a new personality exactly, but definitively a new sense of optimism.

It's not just the music, but the madness that is North America. I truly

enjoy the urban culture and the music of the cities."

"Nobody gave a shit about my background or who my brother was or anything.

I just started with my new songs and my guitar and, I tell ya, it was the time

when I became who I am. I had the music and the ability already, but I

didn't have the confidence. I struggled for too long and became too weighed

down by my own history. In going to America, I severed my connections with

that history and gave myself the opportunity for a completely fresh start."

Does he ever wonder about the validity of discovering his persona in the

anything-goes freedom of a land not known for looking back?

"No", he laughs, "in America, they think history is bunkum and

that has certainly worked in my favour."

Ken Eisner

Los Angeles Times - April 30, 1990

Bloom Adds Humor to His Passion at McCabe's

By CHRIS WILLMAN

You'd think that a singer who renamed himself Luka Bloom after the characters of

Suzanne Vega and James Joyce, respectively--would have more of a sense of humor

than Bloom (ne Barry Moore) evidences on 'Riverside', his earnestly passionate

but not exactly yuk-filled debut album. Luckily, the Gaelic groupies who packed

McCabe's for the Irish folk singer's two shows Friday got to hear Bloom in laughter

as well as Bloom in love.

His romanticism can be weighty on record but was more catching live, in the

context of Bloom's between-song wit and the sheer velocity of some of the fastest,

most forceful 12-string you'll ever hear. Though there was no skimping on the

self-serious material--the worst offender being 'Gone to Pablo', his

mawkish glorification of the suicide of Picasso's lover--Bloom atoned with

a reverent rendition of L L Cool J's gushy rap ballad 'I Need Love'

that put a nice cap on his own more heated romantic odes.

© Los Angeles Times

articles.latimes.com/1990-04-30/luka-bloom

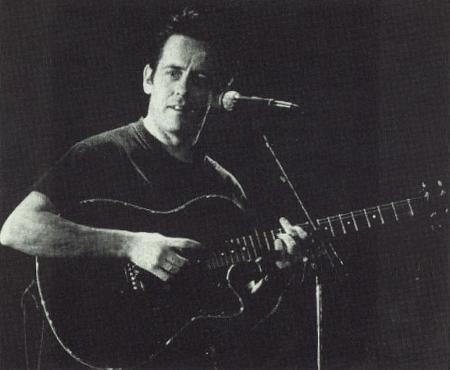

The Rogue Folk Club - May 1990

Luka Bloom @ the W.I.S.E. Hall

The Rogue Folk Club is pleased to present LUKA BLOOM

The Rogue Folk Club is pleased to present LUKA BLOOM

at the W.I.S.E. Hall, 1882 Adanac Street, on Saturday, May 5th.

Doors open at 8:00. Opening the show is Bill Morrissey at 9:00.

Born Barry Moore, brother of Irish folksinger Christy Moore, LUKA BLOOM took his name from the

long-suffering Leopold Bloom, the hero of Joyce's Ulysses, and he's also the inheritor of a particularly Irish

mix of mysticism and moonshine, a carousing spritituality that marks musicians as distinct as Van Morrison

and U2.

Last year LUKA BLOOM was signed to Reprise Records purely on the strength of his live

performances after winning support slots and rave responses on tours with acts like The Pogues,

Sinead O'Connor, Hothouse Flowers, The Violent Femmes and The Proclaimers. His first album,

Riverside, was released in January. |

|

"... (he) did the nearly impossible: held sway over a rowdy, rocking crowd for close 45 minutes

with just an acoustic guitar and his voice, singing well-crafted songs about Picasso, passion, Chile,

and delirium with a warm, beautiful voice and some fine guitar playing ..."

San Francisco Calendar

"Luka Bloom hoots like a steam engine, laughs like a madam, spits out the lyrics and strums

acoustic guitar with the ferocity of a speeding locomotive."

People Magazine

"He can leave you laughing good-naturedly one minute and close to tears the next, linking

one emotion to the next through warm, spirited tales."

The Gavin Report

That live performance is perhaps most notable for the unnerving band-like quality.

LUKA BLOOM is an acoustic rock singer with a sound that seems bigger than

one man and his guitar. As Ireland's Hot Press commented, "For one man and

an instrument, he extracts more sounds and nuances than seem humanly possible."

Tickets are $8 for Club Members, $10 for non-members, and are available at Black Swan,

Track and Highlife Records. Tickets are available at the door, or reserve by calling 736-3022.

Nite Moves - May 1990

Luka Bloom

The night sometimes seems dangerous. We wonder what it hides.

It sometimes brings us closer and forever changes our lives.

- Luka Bloom, 'The Man Is Alive'

The lines were written by a man who gave up his identity, moved to America

and was reborn as - Luka Bloom.

A poet. Though he denies the effect of his written word, prefers to have

them sung, his lines capture the essence of what Luka Bloom represents - the

boy and the man. The coming to terms with, the growth of self.

When Barry Moore made the transition to Luka Bloom, he left behind his

public identity in Ireland to take on a fictitious, and as he called it,

"pretentious" name and identity for his music, in New York.

"It doesn't relate to me personally (his name); it's a totally pretentious

name, it's just an identity for my music."

When Barry Moore made the transition to Luka Bloom, he left behind his

public identity in Ireland to take on a fictitious, and as he called it,

"pretentious" name and identity for his music, in New York.

"It doesn't relate to me personally (his name); it's a totally pretentious

name, it's just an identity for my music."

The songs are structured around life; some, personal introspections,

others, public domain. The rhythm of his acoustic guitar guides the

listener through the plot while his voice gives an emotional account.

'The Man Is Alive', one of the tracks of his debut album Riverside, is a

documentation of his inner struggle to find his father, who died when he was

18 months old. But it's more than that - like so many of his songs. It's an

account of a woman he met, the soul mate.

"Strangers talk in open ways, we cannot always understand."

It reiterates the meeting between Bloom and a woman who lived a paralled

version of his own life. She, Glenda, also lost her father when she was a

baby, 18 months old. The song tells of the meeting, the talk "among the

totem poles underneath the Canadian moonlight / she told me all about her

childhood days on the Vancouver mountainside."

They met for only a few hours, but within that time discovered more about

themselves than each other. It resembles a scene out of a novel by Emily

Bronte: "He's more myself than I am" explains Cathy, the heroine in

Wuthering Heights. Never have those lines had more of an effect than when

you listen to the song and hear Bloom speak of the "magical" meeting of the

twin souls.

Together, Bloom, a writer from Ireland, and Glenda, a songwriter from

Vancouver, find that thread that runs through and parallels our lives to

ones we may never know. A bonding between friends, but it gave them a chance

to look at themselves through the other's life.

It's the kind of gothic realism in Bloom's songs such as 'Dreams In

America', 'The Man Is Alive', the light-hearted stories, 'An Irishman In

Chinatown', and the heart wrenching accounts of life, 'Gone To Pablo' that

make him such a unique artist. His ability to capture an emotion in a word

and hold it through the song.

"When I was 15," Bloom says, "I knew nothing. Now I know I know nothing and

it's alright. The whole purpose of all this is learning. You take up a

little bit and impart it, and you go. You realize how little you know and

carry on and learn some more."

This album is what he's learned about himself and what surrounds him. He's

imparted it and is now carrying on.

S. Decembrini

Folk Roots - July 1990 - No. 85

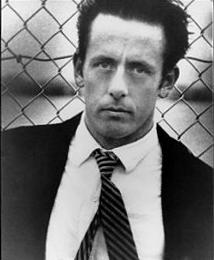

A GOOD LUKA

Ken Hunt hears why Barry made a change

Changing one's name is often rather like making a pact with the devils of expediency. The reasons

are many and various for doing it but, like the snake after sloughing its skin, the emerging creature is

supposed to look brighter, more appealing, at very least different. It may even have grown through the

experience. In some areas of musical endeavour, at certain times, changing one's name has been

de rigeur. Think of Harry Webb, Tommy Hicks and Declan McManus as Cliff Richard, Tommy Steele

and Elvis Costello. Add your own personal favourites.

Luka Bloom as a name may have more of a literary ring to it than most, certainly more so than

those tough, American sounding names in the '50s or the present day heavy metal acts whose stage

names too often sound like bodily functions. Allegedly, 'Luka Bloom' is the quasi-Joycean product of

the marriage between a Suzanne Vega song and the character in Ulysses.

His earlier folk incarnation - Barry Moore - made a couple of albums, Treaty Stone in 1978 and

No Heroes in 1982 and played and sang on Christy Moore's The Iron Behind The Velvet in 1978. Furthermore,

Christy Moore recorded several of his songs, most notably his 'Section 31' and 'The City Of Chicago', while

Moving Hearts covered 'Remember The Brave Ones'.

His earlier folk incarnation - Barry Moore - made a couple of albums, Treaty Stone in 1978 and

No Heroes in 1982 and played and sang on Christy Moore's The Iron Behind The Velvet in 1978. Furthermore,

Christy Moore recorded several of his songs, most notably his 'Section 31' and 'The City Of Chicago', while

Moving Hearts covered 'Remember The Brave Ones'.

To be blunt, his career never really blossomed as he wished. Consequently, like countless Co. Kildare

people before him, he decided to make the move to the Promised Land, in order to try and make his mark.

He uprooted to the United States in October 1987.

Asked about the reason for his change of name, his initial reply may sound a tad evasive: "You know the

reason as well as I do!" On the other hand it is a question which he will be answering for a long time to come.

A 'fuller' answer emerges: "I changed my name because I'd been struggling in Ireland for a number of

years and most of the struggling was to do with myself, finding a musical direction, an attitude that I was

comfortable with. Finding a way of gigging and of working and of writing. I couldn't seem to find it. Some

people take up music and start playing and everything very quickly falls into place for them. I just seemed

to try all sorts of things for years without feeling any comfort at all." While playing folk clubs, bars and pubs,

he was desperately trying to establish what it was he was trying to communicate to his audience. It eluded him for years.

Feeling "no sense of belonging in the folk clubs" put him in a quandary, the solution to which came

along in the mid 80s. The music that fired him, that he wished to gravitate towards, he describes as "early U2,

Waterboys, big-sounding stuff that was very positive but wasn't pompous or bombastic. When I talk about bombastic

I talk about that big classical rock thing that went on in the '70s." Inexplicably, Queen of all people - epitomises this for him.

The first contemporary music that he "hooked into was this early U2, post-punk music that was very melodic,

very aggressive, very raw, but it was positive." Its approach moulded his song writing. He strove "to

write songs with this rawness in mind. I worked for a little while with a band in Dublin; we were called Red Square.

I was working with guys who were ten years younger than me. I was changing, really changing all the time."

Having redefined his territory, as it were, around 1985 or 1986, and convinced himself that he was at long last back

on the right track, he admits that persuading anybody on the Dublin scene of that was more problematical. He felt

trapped there and just as assuredly felt that the British or European folk scenes would not be the key to his salvation.

And lest it be thought that he has overlooked his bloodiness in all this, he recalls that "still being tied in with

Christy Moore" was a contributory factor. Not only that, there was the further confusion of his name sounding

like Gary Moore's. He desperately wanted to start afresh with "a clean slate".

Initially he made New York his base. It proved disagreeable. "It was too hectic, too fast, and I wanted time

to settle into being Luka Bloom. I wanted time to settle into being in America. I wanted time to find some centre

for myself, to begin the process of working." Thus he opted for the comparative peace of Washington DC.

"It was like the folk club thing but I didn't go into a folk club: I went to a bar that put on rock bands, folk bands,

all sorts of different music. Because I didn't want to start out again in a folk club in America. I wanted to find a

venue that was sort of anonymous in a way so I wouldn't be put in a bag immediately, where I could present

my songs in my own way. I just wanted a stage in a room with people." A Wednesday night residency

at "a little club on Bleecker Street called the Red Lion" in New York also helped to get the word around.

Word spread about him - hardly surprising given the strength of his live performances - a process abetted

and speeded by supporting spots for The Pogues during May and June 1988 and Hothouse Flowers during

the following October and November. "In that period I played to 30,000 people twice in 30 cities around

North America. All of a sudden there was this name out there but nobody knew how to contact me."

A mystique developed. "The only way that any of the record companies could get in touch with me was

to look up the Village Voice, see where I was playing and go to the show because I didn't have any

management office or agency representing me. A couple of companies started to come and see me

regularly." This interest resulted in him signing with Warner Brothers in March 1989.

However, his debut album - Riverside - for their Reprise subsidiary

was not his debut recording. Beforehand a track appeared on a 1989 anthology called

Time For A Change for Bar-None Records,

a label with whom the group They Might Be Giants was associated. Bar-None Records became very good

friends and championed his cause but he stuck out for big label interest, even though they became his

managers about two months before the Warners deal. "Recognising that I was going to get a major

deal they asked if they could have one track on the compilation and Warners agreed to it. It was going

to be one track that wasn't on the album, so we picked Trains from a demo that I did."

Now, curiously, the way these things often go, there is a further twist, for antedating both of these releases

was an album released in 1987. The rarity value of Luka Bloom -

"a collector's item" - should not be confused with rare quality, he stresses. "It was done

for an independent label - Mystery Records - and it ran into legal difficulties about three weeks after it was

released and so it was shelved. It was never properly distributed. It sold about 1500 copies. I recorded it

about four weeks before I went to America. lt was released six months later and was out for three weeks

and then it was gone again."

He has no misgivings about the disappearance of 'Luka Bloom', dismissing it as "very misleading",

although he has a fondness for some of its songs. Indeed he went so far as re-recording 'Gone To Pablo',

'Over The Moon' and 'Delirious' for 'Riverside'. Temporarily going into the third-person singular, he

remarks that "Luka Bloom's first album" is 'Riverside'. "I did an album under 'Luka Bloom'

that was never properly released anywhere, so really it's like a demo that leaked."

'Riverside' though, it might justifiably be said, seems directed at America, the same way that Paul

Brady's post-Hard Station albums are. The American experience has clearly coloured Bloom's songwriting,

even if chronologically some of the songs were penned before his departure. Thus 'Gone To Pablo'

with its references to European art galleries seems to adopt a faintly non-European viewpoint in parts.

"An album, to me," he explains, "is more than just a collection of songs. It's like an art

exhibition in that they have to complement each other. I have other songs which I would have loved

to put on the record but they just didn't work as well in the context of the rest of the album. I wanted the

album to have a very broad, dynamic feel to it and a broad range of influences. I wanted it to be

interesting and sustaining. That's why and how I came to pick the songs that I did."

Unlike earlier work, which frequently had a political strand to it, 'Riverside' mostly eschews

such statements. "I didn't really have any material that was politically relevant in the here and

now, at the time of doing the album. I really didn't. The closest thing to a political song that I have

actually got on the album is 'This Is For Life'.

In recent years I have gotten more suspicious and less enthusiastic about political

songwriting. I never really regarded myself as a political songwriter in the first place. Where

I write about political issues it tends to be in the context of people's experience and

individual's experiences of political systems. Very rarely have I sat down to write about

an issue: I'm rarely motivated in that way. I've written a song about AIDS, I haven't a song

about crack dealing because I'm not politically motivated in that way. I have to be viscerally

hit by something; I almost have to experience it. And one of the reasons for that is that I

feel that people too easily these days come to write songs about things and they do it in

a way that is sensationalising. And they do it in a way that I sometimes am suspicious

of because I feel like it's a career move, like people feel a need to have a social

conscience because it sells records. I feel there's been a lot of that, particularly

since Live Aid and the Amnesty International tour."

Two of the strongest songs on the album do, however, have political undercurrents. They make their

statements by using individuals' plights in order to make points of wider relevance. 'This Is For Life'

is a song about a now-failed marriage between one of the Guildford Four and a prison

visitor: "I still sing that song even though Paul HilI's been released because I feel in some way

it's still relevant to any relative of anybody who's doing a life sentence, but I didn't set out to write a

song about political prisoners. Maybe I should. I don't know whether I should or not but I'm trying to

be as honest with you as I can."

The politics of 'The One' are perhaps less apparent. "That's the politics of the voyeuristic

side of the biz. It's something which operates not just in rock & roll but possibly even more so in folk music.

You encounter so many people who would like to claim to have been the person who had the last drink

with Luke Kelly or the last person to have shot up with Jimi Hendrix. It's about this side of the music culture

which wants to see blood. It's where I relate the music industry to boxing, where people want to see somebody

perform, they want to see somebody do really well but they also get a serious kick out of watching them fall.

There are people who want to be right at the front passing up the bottle on stage, bringing the drinks

backstage, providing the drugs in the dressing room." 'The One', he agrees, could be

about any number of music industry figures: its direct inspiration, however, was Shane MacGowan of

The Pogues.

Thematically the album is far from onedimensional. Its best songs are as sleek as an otter's pelt,

although - trapped by metaphor - the lapses can be rather mangey. But 'Dreams In America',

'Gone To Pablo', 'You Couldn't Have Come At A Better Time' and those two

specific songs show that Luka Bloom has clearly arrived in his own right.

Amateur psychologists will probably revel in his motivation for the change of identity, let alone his

striving to develop enough velocity to escape his past. The more musically inclined may well just

find a lot of pleasure in his songs and performances. Stick to the mysteries in the songs.

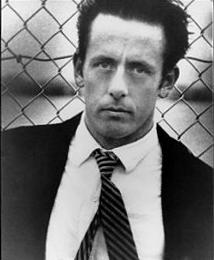

Picture and article from Jolande Hibels

top

The New York Times - August 23, 1991

Sounds Around Town

Luka Bloom @ The Knitting Factory

47 East Houston Street, Manhattan, (212) 219-3055.

The Irish singer and songwriter Luka Bloom is a kind of contemporary folkie: he talks about

love less as youthful passion than as the mature reward that comes after youthful passions

are spent. If he's at times overly earnest, his voice is so rich and confident that you're almost

always tempted to believe what he's saying.

Mr. Bloom performs at midnight tomorrow with a $12 admission.

Karen Schoemers

© 1991 www.nytimes.com

Dirty Linen - December 1991 / January 1992

Ben & Jerry's Newport Folk Festival

Fort Adams Park, Newport, RI

August 10 & 11, 1991

A little over a year ago, driving almost 500 miles from Baltimore to Newport for a two day folk

festival would have seemed madness to me. Now after attending the last two Ben and Jerry's

Newport Folk Festivals, it seems an act of true deprivation not to make this an annual pilgrimage.

This year, blessed with almost perfect weather and an eclectic lineup of folk and roots musicians,

the Festival was another unqualified success...

Sunday, August 11, 1991

Sunday, August 11, 1991

Irish folksinger Luka Bloom put on a truly dynamic solo set that featured both old ("Jacqueline"

and a very energetic "Rescue Mission" that began with a long and impressive rhythmic guitar

introduction) and new (a beautiful encore of "Blue Water") material. The biggest surprise was

the dedication of a tune to his "great grandfather L.L. Cool J", which turned out to be the rap

star's "I Need Love".

Joe F. Compton

© 1991 Dirty Linen

|

|

Later, standard practices continue as this decidedly artful musician ponders

the trappings of his newly-discovered fortune with typically chirpy

bemusements like his Burlington Hotel suite with its round double-bath,

hardly on the Playboy Mansion scale, but far from where he was reared and

the limousine the record company charters to convey him home whereas once,

he took public transport.

Later, standard practices continue as this decidedly artful musician ponders

the trappings of his newly-discovered fortune with typically chirpy

bemusements like his Burlington Hotel suite with its round double-bath,

hardly on the Playboy Mansion scale, but far from where he was reared and

the limousine the record company charters to convey him home whereas once,

he took public transport. I wrote it as a result of encountering for the first time, the vastness and

sheer physical beauty of America because when I travelled with the Hothouse

Flowers we had one long drive through the Rockies. I was just completely

overwhelmed and I suddenly realised that when people talked about the

greatness of America, it wasn't just a right-wing political thing.

I wrote it as a result of encountering for the first time, the vastness and

sheer physical beauty of America because when I travelled with the Hothouse

Flowers we had one long drive through the Rockies. I was just completely

overwhelmed and I suddenly realised that when people talked about the

greatness of America, it wasn't just a right-wing political thing. With a combination of intoxicatingly percussive guitar, a deep bagfull of

haunting melodies, and an unusually thrilling voice, Luka Bloom would be the

freshest thing to hit the folk scene since Suzanne Vega ... if he cared

anything about such a scene.

"I don't like to consider myself part of any traditional music world,"

said the Irish singer/songwriter in a recent call from London, England.

"I seek out stand-up rock audiences, because I like that kind of energy. I'm

not out to soothe some passive crowd of folk worshippers. They have to like

a fair bitta noise: I play acoustic guitar, but I tend to play it loud."

With a combination of intoxicatingly percussive guitar, a deep bagfull of

haunting melodies, and an unusually thrilling voice, Luka Bloom would be the

freshest thing to hit the folk scene since Suzanne Vega ... if he cared

anything about such a scene.

"I don't like to consider myself part of any traditional music world,"

said the Irish singer/songwriter in a recent call from London, England.

"I seek out stand-up rock audiences, because I like that kind of energy. I'm

not out to soothe some passive crowd of folk worshippers. They have to like

a fair bitta noise: I play acoustic guitar, but I tend to play it loud." The Rogue Folk Club is pleased to present LUKA BLOOM

The Rogue Folk Club is pleased to present LUKA BLOOM When Barry Moore made the transition to Luka Bloom, he left behind his

public identity in Ireland to take on a fictitious, and as he called it,

"pretentious" name and identity for his music, in New York.

"It doesn't relate to me personally (his name); it's a totally pretentious

name, it's just an identity for my music."

When Barry Moore made the transition to Luka Bloom, he left behind his

public identity in Ireland to take on a fictitious, and as he called it,

"pretentious" name and identity for his music, in New York.

"It doesn't relate to me personally (his name); it's a totally pretentious

name, it's just an identity for my music." His earlier folk incarnation - Barry Moore - made a couple of albums, Treaty Stone in 1978 and

No Heroes in 1982 and played and sang on Christy Moore's The Iron Behind The Velvet in 1978. Furthermore,

Christy Moore recorded several of his songs, most notably his 'Section 31' and 'The City Of Chicago', while

Moving Hearts covered 'Remember The Brave Ones'.

His earlier folk incarnation - Barry Moore - made a couple of albums, Treaty Stone in 1978 and

No Heroes in 1982 and played and sang on Christy Moore's The Iron Behind The Velvet in 1978. Furthermore,

Christy Moore recorded several of his songs, most notably his 'Section 31' and 'The City Of Chicago', while

Moving Hearts covered 'Remember The Brave Ones'.